If you want to succeed at anything significant in life, setting goals is essential.

Goals are the roadmaps of our lives. They tell us where we are going. They give us a path to get there and may even point out the danger that lays ahead.

Goals can even act as the “fuel” that powers us to our destination. It does this by increasing motivation.

Goals matter. And anyone who wants to achieve success in anything should be setting goals.

This post is a clinical look at goal setting theory and exactly why goals are so important. Enjoy.

Can't get enough of research-based info on personal development and happiness? I invite you to check out Happier Human. It features 53 specific habits that, when applied in your life, increase your personal levels of success and happiness.

Goal Setting Theory: Why goals matter!!

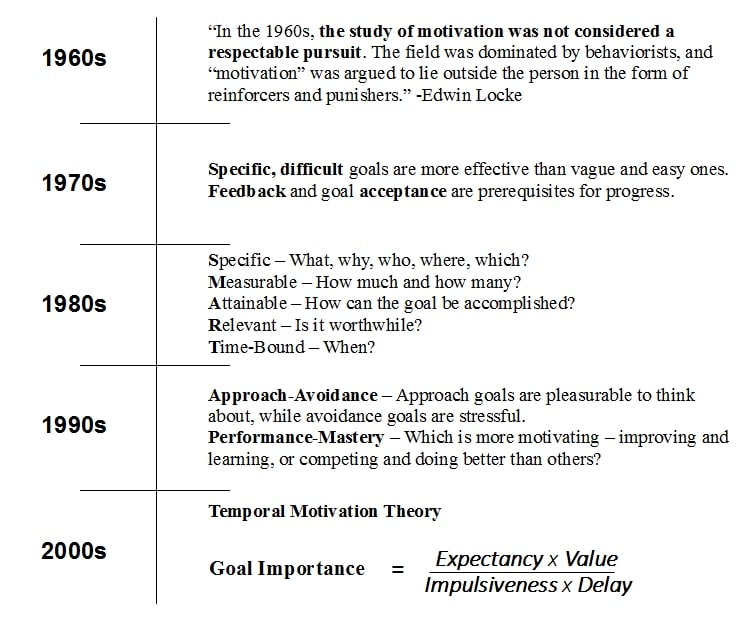

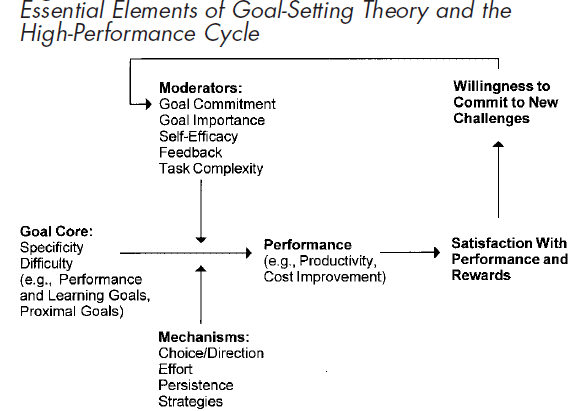

Goal setting is a proven tool for generating motivation. Having been studied extensively for the past 50 years, much is known on how to maximize the tool's usefulness.

Properly set goals have been shown to increase performance on well over 100 different tasks involving more than 40,000 participants in at least eight countries working in laboratory, simulation, and field settings. The variables have included quantity, quality, time spent, costs, job behavior measures, and more. The time spans have ranged from 1 minute to 25 years. The effects have been found using experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational designs. Effects have been obtained whether the goals are assigned, self-set, or set participatively. In short, goal-setting theory is among the most valid and practical theories of motivation in psychology.1

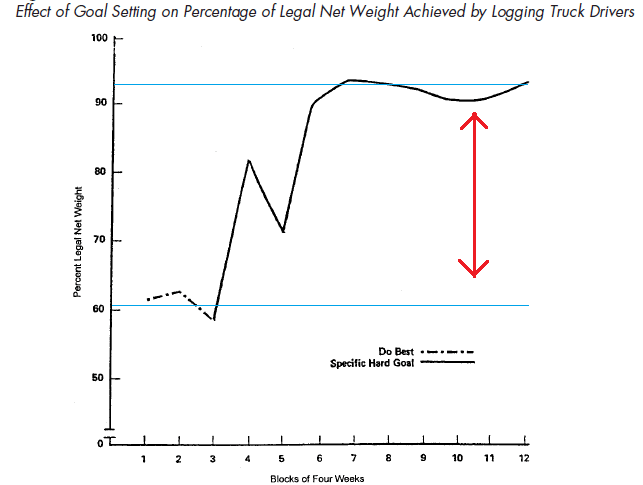

Let's talk money. After goals were assigned to 39 truck drivers, their productivity immediately increased. Over the following 4 months they earned their company an extra $2.7 million dollars.1

After going through a 1-day goal setting workshop, tree loggers immediately started increasing their performance. The additional wood cut over the following 3 months was estimated to be worth a quarter of a million dollars.2

Similarly, significant results have been found with typists, salesmen, dieting, maintenance technicians, chess, students, and many others.3,4,5,6,7,8

Why Do Goals Help?

“Goals affect performance through four mechanisms.

First, goals direct attention and effort toward goal-relevant activities and away from goal irrelevant activities…

Second, goals have an energizing function. High goals lead to greater effort than low goals. This has been shown with tasks that(a) directly entail physical effort,(b) entail repeated performance of simple cognitive tasks, such as addition;(c) include measurements of subjective effort; and(d) include physiological indicators of effort.

Third, goals affect persistence. When participants are allowed to control the time they spend on a task, hard goals prolong effort.

Fourth, goals affect action indirectly by leading to the arousal, discovery, and/or use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies.”22

Goal Selection

In comparing goal selection with goal motivation, although the same variables are involved, they often act in different ways.

For example, a person might shy away from a goal involving frequent feedback – the anxiety of being watched or reviewed might be aversive. However, once selected, frequent feedback is an essential component of successful goal pursuit.

Desire – Economists Are Wrong, Humans Aren't ‘Rational'

According to economists, goals are selected in order to maximize expected value – people eat 1,000 calorie desserts because the pleasure they provide outweighs the risk of heart disease. Perhaps it does, but in most circumstances, humans are irrational. That is, they act sub-optimally. For example, humans get more pleasure out of socializing than from watching TV.59 Then why does the average American spend 4 hours a day in front of the tube? Irrationality – the shiny screen appeals more strongly to our desire.

Goal setting is based more on the crude forecasting of our subconscious, as expressed through desire, than on maximizing expected value.60

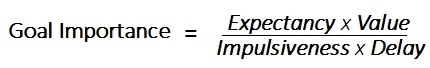

Temporal Motivation Theory

According to Piers Steel, the world's leading procrastination researcher, goal importance is subconsciously calculated using the following formula:

- Expectancy: The percent likelihood of success, as judged by your subconscious.

- Value: The desirability of the expected reward, as decided by your subconscious.

- Impulsivity: The strength of one's tendency to act on a whim.

- Delay: The expected time until the reward will be acquired.

Expectancy Theory: Expectancy x Value

“Expectancy theories suggest that a process akin to rational gambling determines choices among courses of action. For each option, two considerations are made: (1) what is the probability that this outcome will be achieved, and (2) how much is the expected outcome valued?”11,12

This theory is well-supported.14,15 However, two caveats are necessary. First, the accuracy of the model brakes down over large periods of time, useful only in predicting short-term decision making.13,15 However, this is why the second component of temporal motivation theory includes present value discounting. Second, value is determined more by the subconscious, than by what a person ‘logically' decides is important.

More on expectancy theory on wikipedia.

Prospect Theory

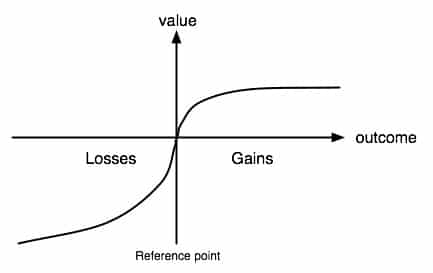

Even if two goals present the same outcome, if the goal is phrased as a loss it will be perceived as more important.16

For example, consider a person who needs to purchase a gift on a $100 budget. They can choose between:

- Saving $50 by spending 3 hours shopping.

- Earning an extra $50 by working for 1 hour.

Financially, the goals are the same – what would have been a loss of $100 becomes $50. However, even when all the other variables are the same (e.g. the person likes working as much as shopping) the first choice is more likely to be selected than the second.

For example, 93% of PhD students registered early when a penalty fee for late registration was emphasized, with only 67% doing so when this was presented as a discount for earlier registration.17

More on prospect theory on wikipedia.

Present Value Calculation: Delay x Impulsivity

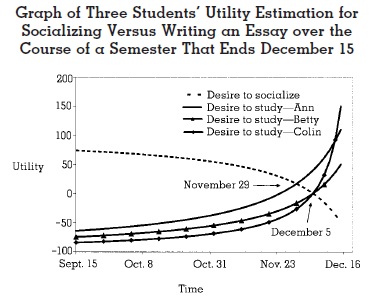

The primary reason that college students procrastinate is because of delay. The paper or report is unimportant until the last moment, once the deadline is just a few hours away. Worse, getting those good grades is helpful, but only for getting a job, something years into the future. Most people would rather receive $100 now than $110 after a year. Now is better.

This is because humans evolved to develop a present-focus time perspective. In an ancestral environment, someone spending the first 21 years of their life on education would have died. There were more pressing concerns – hunting for food, building shelter, staying safe, and so on. According to Philip Zimbardo, who studies the psychology of time, humans are born into the world with a present-focus time perspective. Although kids might intellectually understand the importance of studying for the future, their primitive brain disagrees, resulting in temper-tantrums about being forced to do something so boring, like homework.

As they age, children become less impulsive (in part because their prefrontal cortex matures, and in part because of cultural pressure). On a subconscious and emotional level, they start to understand the importance of working not just for the present, but for the future. For those who are less impulsive, delay is less important – $110 after a year is just as good as $100 today. For those who are more impulsive, pleasure now is priority number one.

As you can see in the picture above, as the deadline becomes closer the goal of writing the essay becomes more and more important.12 In addition, because Ann is less impulsive, she starts working on the paper earlier than the other students.

Feedback

To some degree, all people have evaluation anxiety.18 This is obvious when one considers that although feedback has such a transformative impact, most people do not seek it out. For example, websites which offer the opportunity to anonymously collect personal feedback (e.g. you talk too loud, have poor fashion sense, make unfunny jokes, etc…) are extremely useful but are used by very few people. Because that feedback chips away at self-esteem, it is avoided.

Likewise in the workplace. Although the annual review leads to greater performance, few people enjoy the process. Fewer still actively seek out feedback during the intermittent 12 months between each review. Examples can be found in all other domains. People are less likely to select goals which produce anxiety. The prospect of evaluation is one of the, if not the largest source of potential anxiety.

Fantasy Visualization

According to fantasy visualization theory, there are three routes through which goals are subconsciously set.

Expectancy Based

“The expectancy based route rests on mentally contrasting positive fantasies about the future with negative aspects of impending reality. This mental contrast ties free fantasies about the future to the here and now. Consequently, the desired future appears as something that must be achieved and the impending reality as something that must be changed. The resulting necessity to act raises the question: can reality be altered to match fantasy? The answer is given by the subjective expectation of successfully attaining fantasy in reality. Accordingly, mental contrasting of positive fantasies about the future with negative aspects of the impending reality causes expectations of success to become activated and used. If expectations of success are high, a person will commit herself to fantasy attainment; if expectations of success are low, a person will refrain.”19

Fantasy Based

“The second route to goal setting stems from merely indulging in positive fantasies about the desired future, thereby disregarding impeding reality. This indulgence seduces one to consummate and consume the desired future envisioned in the mind’s eye. Accordingly, no necessity to act is experienced and relevant expectations of success are not activated and used. Commitment to act towards fantasy fulfillment reflects solely the pull of the desired events imagined in one’s fantasies. It is moderate and independent of a person’s perceived chances of success (i.e. expectations). As a consequence, the level of goal commitment is either too high (when expectations are low) or too low (when expectations are high).”19

Negative Rumination

“The third route is based on merely dwelling on the negative aspects of impending reality, thereby disregarding positive fantasies about the future. Again, no necessity to act is experienced, this time because nothing points to a direction in which to act. Expectations of success are not activated and used. Commitment to act merely reflects the push of the negative aspects of impending reality. Similar to indulgence in positive fantasies about the future, dwelling on the negative reality leads to a moderate, expectancy independent level of commitment, which is either too high (when expectations are low) or too low (when expectations are high).”19

See Seven Steps to Reducing Rumination

Core Concepts of Effective Goal Setting

There are four components of goal setting which must always be in place for the process to be effective:

- Goal Excitement & Acceptance – The goal must contain a reward valuable enough to make the effort worth it.

- Goal Difficulty – Hard, challenging goals are inspiring, while easy goals are not.

- Goal Specificity – Within reason, the more specific the better.

- Goal Feedback – The better and more frequent the feedback, the faster the progress. Without feedback, progress is impossible.

In addition, there are the avoidance-approach and mastery-performance dichotomies to select from.

Goal Excitement & Acceptance

Exciting, accepted goals are motivating goals:

- Hard goals are more exciting than easy goals.

- A reward that sounds good now might feel pointless upon reflection.

- The most powerful reward is worthless if forgotten.

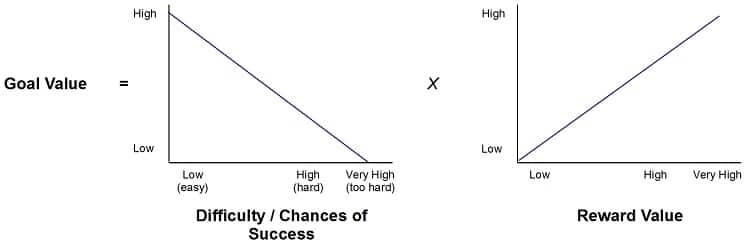

1. Hard Goals Are More Exciting Than Easy Goals

People are often encouraged to have realistic expectations. If the purpose is to inspire motivation, that advice is false.

Difficult goals inspire greater performance than easy goals. This is true for two reasons. One, “we are motivation misers,” which is discussed in the next section.20 Two, difficult goals lead to larger rewards. What's more exciting? The prospect of earning a million dollars, or the prospect of earning ten?

As described by expectancy theory in the last section, people are less likely to select difficult goals. However, once chosen difficult goals are more motivating than easy ones.

2. A Reward That Sounds Good Now Might Feel Pointless Upon Reflection

As humans were evolved to be short-sighted, the human mind is poor at long-term planning. Known as the optimism bias, humans have a strong tendency to underestimate the difficulty of accomplishing their goals. The human mind has a hard time changing the abstract notion of long-term, hard work into a concrete estimate of the time and energy required.

After having that optimism shattered by the strain of reality, a reward than once seemed exciting may no longer appear worthwhile. On a crude level, excitement and desire is a function of expected reward minus expected cost. Becoming a doctor and earning $150,000 a year? Not worth seven years of 80-hour weeks. Getting into shape? Worth exercising twice a week.

Because we tend to underestimate effort, we overestimate excitement. In other words, we feel excited about the goals that we shouldn't. As the optimism bias is hard-coded into our brain, it's difficult to overcome, although mental contrasting can help.

The simple solution is to select only those goals which are extra-exciting, which offer a reward that is strongly desired. I personally have abandoned many goals because of this problem. Although the reward was exciting enough to get me started, once I realized just how hard I was going to have to work, the reward was no longer enough.

3. The Most Powerful Reward is Worthless if Forgotten

The human brain is poorly equipped to handle many modern sources of motivation. The more we put off acquiring food, the hungrier we get and the more motivated to eat we become. Likewise with social connectivity. The longer we go without contact, the stronger the motivation to connect becomes.

Now consider a modern source of motivation, like power and wealth. After an inspiration speech, we feel the excitement. But as time passes without our having taken any action, unlike with hunger and social connectivity, instead of motivation increasing, it rapidly falls to zero. The problem is this – the human brain is used to getting reminders. Lack of wealth can be as motivating as lack of food, but the body doesn't produce a lack of wealth reminders.

Hunger, loneliness, thirst, cold – all reminders which get produced automatically. Don't act, and the reminder gets louder and the motivation stronger. But with wealth, well-being, health, and many other modern goals, reminders don't get produced automatically – that's what motivational speeches and inspirational writing are for.

This is why the most powerful reward is worthless if forgotten, and why [fantasy visualization] is so frequently recommended. Not only should an exciting goal be selected, but the reason(s) why it's exciting needs to be frequently reviewed – we need to create our own reminders.

Goal Difficulty

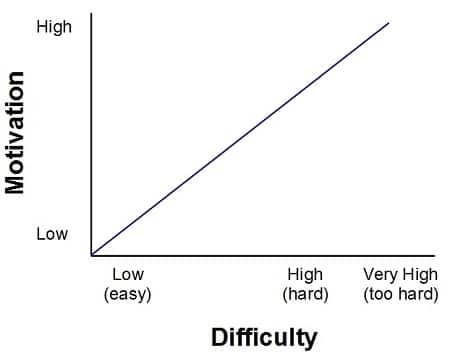

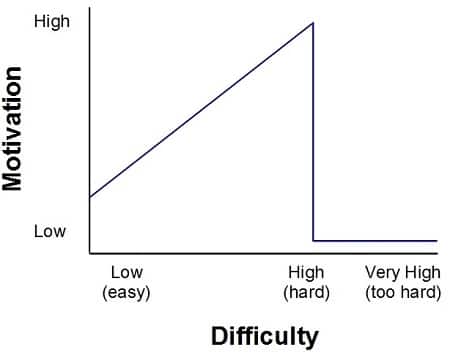

Hard, challenging goals are motivating, while easy goals aren't.36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53

When selecting a goal, difficulty is aversive – we stay away from uncertainty. After having actually selected a goal, difficulty is energizing.35

Negative Expectancy Model

In order for a more difficult goal to be accomplished, more energy must be expended, as skills need to be improved and hard work needs to be put in. Energy is functionally equivalent to motivation – more energy equals more motivation.

On the other hand, if success is all but guaranteed, it would be a waste to allocate more than the minimum (e.g. there’s no point getting excited and motivated about the goal of eating breakfast – that’s a waste of mental energy. If someone wants to eat breakfast, it will probably happen, excitement and motivation or not).

We are motivational misers who constantly fine-tune our effort levels so that we strive just enough for success.20

However, this picture is incomplete.

Discontinuous Expectancy Model

Motivation is low for easy goals because the brain is frugal – there is no point getting excited and wasting energy on something simple and easy, like eating breakfast, taking a shower, or sending an e-mail. As goal difficulty increases, motivation rises in step – for example, getting a training certification requires more energy than taking a shower, which the brain provides by increasing motivation.

However, after a certain level of difficulty, motivation immediately drops to near zero, as people feel that the task is too challenging – that even with a high level of motivation, their resources or abilities are not enough.

Goal Specificity

“Twenty four field experiments all found that individuals are given specific, challenging goals either outperformed those trying to “do their best”, or surpassed their own previous performance when they were not trying for specific goals.”21

Simply, specific goals are more effective than vague ones.2,3,9,10,22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34

In one study, engineers and scientists were told to do their best. In another, unionized telecommunications employees were told to do their best. For both groups, those who were instead told to hit a specific target did better, receiving higher ratings and also reporting higher job satisfaction.9,10

When people are asked to do their best, they do not do so. This is because do-your-best goals have no external referent and thus are defined idiosyncratically. This allows for a wide range of acceptable performance levels, which is not the case when a goal level is specified.22

There are four major reasons why specific goals are so much more effective than vague ones:

- It is easier to get feedback for specific goals, and feedback is one of the most important requirements for progress. For example, one could have the goal of getting more fit. Without having defined what ‘fit' means, progress is difficult to gauge. On the other hand, if the goal is structured as being able to run 2 miles and having biceps with a diameter of 14″ within the next 3 months, one can immediately know how they're doing, what's working, what isn't, and if they need to make any changes.

- Specificity leads to planning. At the high level of ‘getting fit', it's difficult to effectively strategize, “I want to get fit… so I'll go running!”. To create an effective strategy requires a clear idea of the objective. If the goal is to be able to run 2 miles within 3 months, an effective strategy can be created, “I will follow this 3-month training plan, running half a mile tomorrow, 3/4ths a mile next week….”

- Specificity is exciting. The more specific the goal, the more vivid your thoughts when imagining the goal. The more vivid your thoughts, the more real & exciting. Which goal do you think is more likely to generate excitement? “I will get fit and look sexy” or “I will lose 10 pounds, tone my abs, fit into pants two sizes lower and look sexy”?

- The more specific your goal, the more you'll be practicing it mentally. Habits are powerful – whether bad (nail-biting) or good (brushing teeth) – they make action automatic and often effortless. Mental practice contributes to habit formation. If you have a specific goal, when you think about that goal, you might also be doing mental practicing, in turn helping to form a habit and making the goal easier to accomplish.

Goal Feedback

“Integrating the two sets of studies points to one unequivocal conclusion: neither [feedback] alone nor goals alone is sufficient to affect performance. Both are necessary. Together they appear sufficient to improve task performance.”22

“For goals to be effective, people need summary feedback that reveals progress in relation to their goals. If they do not know how they are doing, it is difficult or impossible for them to adjust the level or direction of their effort or to adjust their performance strategies to match what the goal requires. If the goal is to cut down 30 trees in a day, people have no way to tell if they are on target unless they know how many trees have been cut. When people find they are below target, they normally increase their effort or try a new strategy.”21

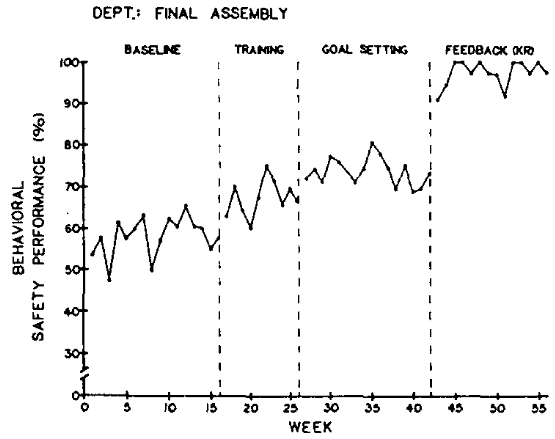

In one study, the effect of goal feedback on improving health-safety compliance was measured. Before goals were set and feedback was provided, compliance was around an abysmal 60%. Afterward, compliance hit 100%.26

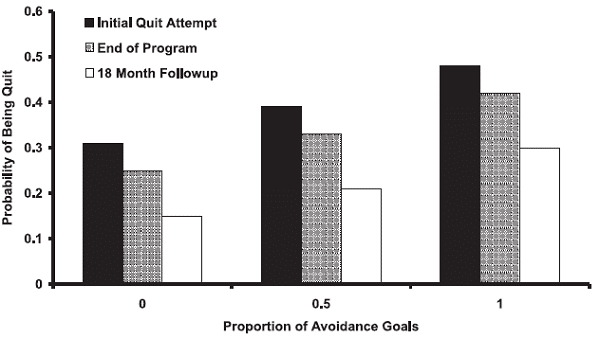

Approach vs. Avoidance

Goals can be either approach or avoidance. They can also be both, although that is rare and is discussed at the end of this section.

| Approach | Avoidance |

|---|---|

| I will lose weight so that I can look good. | I will lose weight so that I can stop looking ugly. |

| I will score the highest in my class. | I will avoid scoring low. |

| I will learn how to get my work done faster and better. | In order to avoid getting yelled at by the boss, I will stop working slowly. |

Approach goals are usually pleasurable to think about, while avoidance goals are stressful.23

Stress can be an exceptionally powerful motivator but is sometimes used in place of what would have been an equally effective excitement. For example:

“I will study to avoid getting yelled at” vs. “I will study in order to feel good about my capabilities.”

Both might have produced a similar outcome – getting good grades, but undeniably the second perspective would be more enjoyable. However, avoidance goals are usually more emotionally powerful than approach goals – the thought of getting yelled at is a more emotionally charged experience than the thought of doing well. Recall prospect theory.

The reason avoidance goals are not universally more effective is because they’re sometimes too emotionally charged – thinking about the goal produces so much stress and anxiety, that in an attempt to feel better and get distracted, people procrastinate. Even when effective, the cost can sometimes be high. For example, jobs which are high in avoidance motivation have higher turnover.23

For these reasons, psychologists believe that approach goals are more effective than avoidance goals. However, there are several important nuances.

First, in some domains, avoidance goals appear to more effective than approach goals. For example, in a study of smokers attempting to quit, those instructed to write down an avoidance goal had more success than those instructed to write down an approach goal.24

“As with traditional conceptualizations of avoidance goals, some avoidance goals involve preventing a negative state from occurring (e.g., I do not want to get cancer). However, other avoidance goals involve curing a negative state that already exists (e.g., I want to get rid of a chronic cough)…

Researchers have argued that trying to stay away from a state elicits anxiety, which in turn undermines how much effort people will put forth to work on the goal. Moreover, even if progress is made on a prevent goal, the difficulty of detecting the continued absence of something may make the progress hard to recognize.

For example, people trying to prevent developing cancer may find it difficult to detect a reduction in the risk of developing cancer and thus have a hard time determining whether they have made any progress on their goal. In contrast, to prevent goals, it may be easier to detect progress when working to meet a cure-avoidance goal.”

Similar results were found in another study – for health goals, cure-avoidance goals are more likely to motivate proactive health behavior (e.g. going to the doctor's).24 In my own life, avoidance-cure motivation has been more effective in fighting my fibromyalgia than approach motivation.

Second, avoidance goals can sometimes be combined with approach goals, so that the total motivation increases while stress decreases.22

For example, I have made a pledge that if I don't finish this article by the end of the day, I will have to donate $150 to charity. That's stressful – I want to avoid losing money. At the same time, it's exciting – I want to work hard in order to share my knowledge. For the goal of writing this article, I have two sources of motivation – one approach and one avoidance.

Performance vs. Mastery

Do you think of your goals in terms of doing better than others or in terms of learning?

| Learning | Performance |

|---|---|

| I will score higher than last time. | I will score the highest in the class. |

| I will exercise three times a week. | I will become the fittest member of my family. |

| I will learn how to get my work done faster and better. | I will get the best performance review out of everyone on my team. |

The thought of doing better than others can be exciting and motivating. But the thought of doing worse can be unsettling. Distracting, even.

The thought of improving and learning can also be exciting and motivating, so the question is, which is more motivating – improving and learning, or competing and doing better than others?

Psychologists tend to lean towards learning goals, as in most of the studies they've conducted, those with a learning goal have done better than those with a performance goal.

“People with performance goals seek to prove their ability. When people with performance goals encounter stressful situations, they seek to avoid proof of low ability, which they associate with low self-worth. In contrast, people with learning goals (also known as mastery goals) seek to develop and improve their ability. When people with learning goals encounter stressful situations, they seek to learn and grow from the experience…

The two types of goals are associated with different strategies for dealing with negative feedback. People with performance goals tend to use defensive strategies for dealing with failure or rejection, including withdrawing effort, making excuses, and avoiding challenging tasks. People with learning goals tend to use constructive strategies for dealing with failure or rejection, including increasing effort, persisting on difficult tasks, seeking help, and remaining open to information about their mistakes.”

However, once performance goals are split into performance-approach and performance-avoidance (e.g. I will do the best vs. I will avoid doing the worst), in certain circumstances and for certain people, performance-approach goals are more effective than mastery goals.22 Personally, I find the prospect of competition exciting and motivating. Many of the skills I've learned and the knowledge I've gained has been in order to do well in the competition.

More research is necessary to tease out the specific circumstances and personality traits for which performance goals are more effective than learning goals.

Goal Setting Risks

Read Goals Gone Wild for a review of the risks of goal setting.

Disheartenment

“When the goal is very difficult, paying people only if they reach the goal (i.e., a task-and-bonus system) can hurt performance. Once people see that they are not getting the reward, their personal goal and their self-efficacy drop and, consequently, so do their performance. This drop does not occur if the goal is moderately difficult or if people are given a difficult goal and are paid for performance (e.g., piece rate) rather than goal attainment.”22

Goodheart's Law / Tunnel Vision

When a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure.56

“Achievement tests may well be valuable indicators of general school achievement under conditions of normal teaching aimed at general competence. But when test scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.55“

In order to hit their requirement and keep their job, consider two different ways a teacher could raise the test scores of their children. One, they could spend an extra three hours every day working – some extra time for lesson planning, some time for staying after school and offering free tutoring, and so on. Two, they can try to anticipate what the test questions will be and have their students memorize their answers. Because two is significantly easier, the teacher will probably select that option.

If the test was a perfect measure of student progress, that would be okay. But because it isn't, now that test scores have become a goal target, they've stopped being an accurate measure of student progress, as teachers and students “game” the system. The size of the degradation varies from measure to measure.

The real-world consequence is that a goal might cause someone to become less, rather than more productive. Consider a goal to get a better review, in a situation where the busiest people in the office tend to get the highest reviews. While people aren't gaming the system, that correlation makes sense – those who work harder tend to perform better. But with a goal of getting a better review, although one option is to do more work, the easier option is to spend a little extra effort to always look busy.

Self-set goals rarely have this problem, Goodheart's Law is more a concern for managers.

Unethical Behavior

“We explored the role of goal setting in motivating unethical behavior in a laboratory experiment. We found that people with unmet goals were more likely to engage in unethical behavior than people attempting to do their best. This relationship held for goals both with and without economic incentives. We also found that the relationship between goal setting and unethical behavior was particularly strong when people fell just short of reaching their goals.57“

Risky Behavior

In one study, participants who were given difficult performance goals selected riskier strategies, as they needed to improve performance in order to meet their targets.58

Combined with survivorship bias, this problem is a large contributor to company failure.

Goal Setting Theory Review

Hopefully, this post clears up any idea of the overarching importance of goal setting.

This blog is about what it takes to be happy and goal setting is indirectly a key to happiness. Setting goals is not directly one of the 54 Ways to be Happy. But many of the tools for happiness may require some goal setting and planning to achieve. Goal setting itself does not bring happiness, but achieving the right things will bring a sense of accomplishment that does help to secure happiness.

So work on those goals in your life. The things that matter, not just making more money, and get closer to happiness.

If you want to learn more about goal setting, check out our timeline of goal setting research.

Lastly, if you can't get enough of research-based materials on personal development and happiness, check out the book Happier Human. It features happiness habits that are proven by research to make you happier.

Goal Setting Theory References

1. The Importance of Union Acceptance for Productivity Improvement Through Goal Setting, 1982.2. Improving Job Performance Through Training in Goal Setting, 19753. Effects of Assigned and Participative Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976.4. Effects of Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976.5. The Role of Proximal Intentions in Self-Regulation of Refractory Behavior, 1977.6. Different Goal Setting Treatments and Their Effects on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1997.7. Additive Effects of Task Difficulty and Goal Setting on Subsequent Task Performance, 1976.8. The Relationship of Procrastination With a Mastery Goal Versus an Avoidance Goal, 2009.9. Joint Effect of Feedback and Goal Setting on Performance: A Field Study of Residential Energy Conservation, 1978.10. The Effects of Goal Setting and Self-Instruction Training on The Performance of Unionized Employees, 2000.11. Expectancy Theory Predictions of Salesmen’s Performance, 1974.12. Integrating Theories of Motivation, 2006.13. Motivation Theory, Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1990.14. Self-Efficacy and Resource Allocation Support For a Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model, 2008.15. Vroom’s Expectancy Models and Work-Related Criteria: A Meta-Analysis16. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice, 1981.17. The Power of Reframing Incentives: Field Experiment on (Students') Productivity, 2008.18. Evaluation Anxiety. Handbook of Competence and Motivation, 2005.19. Goal Selection and Goal Striving. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology, 2001.20. The Procrastination Equation: How to Stop Putting Things Off and Start Getting Stuff Done, 2010.21. Goal Setting and Task Performance, 198022. Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation, 2002.23. The Hierarchical Model of Approach-Avoidance Motivation, 2006.24. Avoidance Goals Can Be Beneficial: A Look at Smoking Cessation, 2005.25. A 2 x 2 Achievement Goal Framework, 2001.26. Improving Safety Performance With Goal Setting and Feedback, 1990.27. Changes in Performance in a Management by Objectives Program, 1974.28. Assigned Versus Participative Goal Setting With Educated and Uneducated Woods Workers, 1975.29. Effects of Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976 (sales personnel).30. Effect of Performance Feedback and Goal Setting on Productivity and Satisfaction in an Organizational Setting, 1976.31. The Role of Proximal Intentions in Self-Regulation of Refractory Behavior, 1977.32. Performance Standards and Implicit Goal Setting: Field Testing Locke’s Assumption, 1977.33. Blue Collar to Top Executive, 1977 (ship loading).34. Different Goal Setting Treatments and Their Effects on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1977 (maintenance technicians).35. Personal Correspondence With Piers Steel.36. Increasing Productivity With Decreasing Time Limits: A Field Replication of Parkinson’s Law, 1975.37. Interrelationships Among Employee Participation, Individual Differences, Goal Difficulty, Goal Acceptance, Goal Instrumentality, and Performance, 1978.38. A Study of The Effects of Task Goal and Schedule Choice on Work Performance, 1979.39. Knowledge of Score and Goal Level as Determinants of Work Rate, 1969.40. Studies of The Relationship Between Satisfaction, Goal Setting, and Performance, 1970.41. The Effects of Participation in Goal Setting on Goal Acceptance and Performance, 1975.42. A Two-Factor Model of The Effect of Goal-Descriptive Directions on Learning From Text, 1975.43. Additive Effects of Task Difficulty and Goal Setting on Subsequent Task Performance 1976.44. Role of Performance Goals in Prose Learning, 1976).45. The Motivational Strategies Used by Supervisors: Relationships to Effectiveness Indicators, 1976.46. Effects Achievement Standards, Tangible Rewards, and Self-Dispensed Achievement Evaluations on Children’s Task Mastery, 1977.47. Systems Analysis of Dyadic Interaction: Prediction From Individual Parameters, 1978 .48. The Interaction of Ability and Motivation in Performance: An Exploration of The Meaning of Moderators, 1978.49. Effects of Goal Level on Performance: A Trade-off of Quantity and Quality, 1978.50. Importance of Supportive Relationships in Goal Setting, 1979.51. The Effects of Holding Goal Difficulty Constant on Assigned and Participatively Set Goals, 1979.52. The Effect of Beliefs on Maximum Weight-Lifting Performance, 1979.53. Another Look at The Relationship of Expectancy and Goal Difficulty to Task Performance, 1980.54. Performance and Learning Goals for Emotion Regulation, 2011.55. Assessing the Impact of Planned Social Change, 1976.56. Problems of Monetary Management: The U.K. Experience, 1975.57. Goal Setting as a Motivator of Unethical Behavior, 2004.58. The Relationship of Team Goals, Incentives, and Efficacy to Strategic Risk, Tactical Implementation and Performance, 200159. A Survey Method for Characterizing Daily Life Experience: The Day Reconstruction Method, 200460. Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011.

Great article with lots of practical tools and references for goals setting and its impact on human behviour.